Encopresis and Enuresis: Cognitive Behavioral Play Therapy

Elimination Disorders

What are Elimination Disorders?

Elimination disorders involve the inappropriate discharge of urine or feces and are usually first diagnosed in childhood. This group of disorders includes enuresis, the repeated passage of urine in inappropriate places, and encopresis, the repeated passage of feces in inappropriate places. As noted above, elimination disorders include ENURESIS and ENCOPRESIS.

Enuresis

- Repeated voiding of urine into bedclothes or clothes.

- Urine passage may be involuntary or intentional.

- The behavior is clinically significant when it occurs at least twice a week for at least three consecutive months.

- The child may restrict social activities (e.g., be unable to participate in sleepovers), and such limitations can affect the child’s self-esteem.

It is important to specify whether enuresis is:

- nocturnal only (urination only during sleep),

- diurnal only (urination during waking hours),

- nocturnal and diurnal (both day and night).

Encopresis

- Repeated passage of feces in inappropriate places (e.g., in clothing or on the floor).

- Fecal passage may be intentional or involuntary (involuntary episodes are often related to constipation).

- The child often feels shame and may avoid situations (e.g., camping or school) that could cause embarrassment.

- Fecal incontinence occurs at least once a month for at least three months.

When do Elimination Disorders occur?

Elimination disorders usually occur separately but can sometimes co-occur. Enuresis is typically diagnosed between 5 and 8 years of age, whereas encopresis is not diagnosed until the child has reached a chronological age of at least 4 years.

What are the causes of Elimination Disorders?

Causes are typically multifactorial and differ by disorder.

ENURESIS – CONTRIBUTING FACTORS

- Environmental factors: delayed or inconsistent toilet-training practices and psychosocial stress.

- Genetic and physiological factors: delayed maturation of normal circadian rhythms of urine production leading to nocturnal polyuria, reduced functional bladder capacity, or bladder overactivity.

- Psychological factors: low self-esteem and social marginalization by peers may exacerbate enuresis.

ENCOPRESIS – CONTRIBUTING FACTORS

- Inadequate or contradictory toilet-training practices.

- Psychosocial stressors: for example, school entry or the birth of a sibling.

- Genetic and physiological factors: painful defecation can lead to constipation and cycles of stool withholding that increase the likelihood of encopresis.

- Psychological motivations: anxiety about defecating in a particular place or an anxious/oppositional behavioral pattern; in cases of constipation, such motivations can lead to avoidance of defecation.

Enuresis and Encopresis Cognitive Behavioral Play Therapy (CBPT)

Cognitive Behavioral Play Therapy (CBPT) is an approach that targets behavior and thought patterns while making the child an active participant in change. CBPT is a structured, brief, goal-oriented therapy whose objectives are shared with the child and family. The child is welcomed into a play setting designed to build the therapeutic alliance, and parents follow a parallel pathway aimed at learning and strengthening parenting competencies.

The intervention is organized into the following phases:

- ORIENTATION PHASE: This initial phase emphasizes preparation of both child and parents. An intake meeting with the parents (without the child) gathers detailed history and background information and allows parents to share their perception of the problem. The therapist helps parents prepare the child for the first session and explains the ongoing role of parents and other significant adults in assessment and treatment. Although the focus is on the child during CBPT, the therapist continues to interact regularly with parents to offer support and evaluate progress toward therapeutic goals.

- ASSESSMENT PHASE: This phase focuses on collecting crucial information to establish therapy goals. In addition to parent interviews, a key element is observation of the child’s play. Tools may include parent questionnaires, assessment of the child’s play, family play assessment, the puppet sentence-completion task, and other measures personalized by the therapist. The therapist may establish a baseline for the frequency of elimination-related behaviors to evaluate change over treatment.

- CASE CONCEPTUALIZATION PHASE: CBPT begins with analysis of assessment data to plan an effective treatment and provide a logical structure for developing and achieving therapeutic goals. The therapist explains the elimination disorder, analyzes individual, relational, and environmental factors related to parental concerns, and examines the child’s emotions, thoughts, bodily sensations, and coping strategies. This phase also includes analysis of protective, risk, and maintaining factors that contribute to the child’s behavior.

- INTERVENTION PHASE: The intervention phase focuses on CBT techniques adapted to play that help the child develop more adaptive responses to problems, situations, and stressors. Emphasis is on learning adaptive thoughts and behaviors. Methods include modeling, role-playing, bibliotherapy, generalization, and relapse prevention. Interventions often adapt traditional cognitive techniques through play tools such as drawing and expressive arts, therapeutic storytelling, or interaction with puppets facing similar situations. Treatment includes strategies to help the child generalize skills learned in sessions to other contexts and to work on relapse prevention. Although the primary focus is the child, regular meetings with parents are important to monitor progress, address parent–child interactions, and provide guidance.

- CONCLUSION PHASE: Both child and family are actively involved in the final phase. The child processes feelings related to therapy termination while the therapist highlights changes and consolidates learning. Final sessions may be spaced out (weekly to biweekly to monthly) to help the child perceive their ability to manage without the therapist. The therapist reinforces progress between sessions and normalizes separation. Follow-ups are scheduled at 3, 6, 12, and 24 months to verify intervention effectiveness.

What are the Therapeutic Goals in the treatment of Enuresis and Encopresis?

Two primary goals are CONTROL and MASTERY of toileting. These goals are achieved by working on:

- Modeling

- Prevention of exposure and response

- Positive reinforcement

- Modeling socially appropriate expression of feelings

- Identifying maladaptive beliefs

- Changing maladaptive beliefs

- Positive self-statements

What can Parents do?

It is essential that parents of children with elimination disorders understand the factors contributing to the child’s symptoms, the environmental cues and events that trigger fear or avoidance of toileting, and behavior-management strategies that improve the child’s control and mastery.

Parents should be supported, once diapers or absorbent training pants are discontinued, not to revert to earlier toileting practices.

ENHANCE YOUR CHILD PSYCOTHERAPY SKILLS

COGNITIVE BEHAVIORAL PLAY THERAPY TRAINING

Parent Training in Enuresis and Encopresis

What is Parent Training?

Parent Training is a competence-based intervention model that starts from the assumption that families are able to manage and address the problem, that every family has strengths, and that they can learn.

Parent training embedded within Cognitive Behavioral Play Therapy emphasizes the importance of involving parents in the playroom setting, where they have the opportunity to observe and progressively implement interventions to shape adaptive behaviors in the presence of the therapist. It highlights parents’ adaptability and learning capacity and aims to modify relational styles and attitudes that negatively influence children’s behaviors.

What Parents can gain?

Through this approach, parents have the opportunity to:

- Learn new skills

- Acquire and practice specific techniques

- Receive individualized, ongoing feedback from the therapist to help them become more aware

- Learn to interpret more accurately their children’s emotions, concerns, and communication as expressed through play

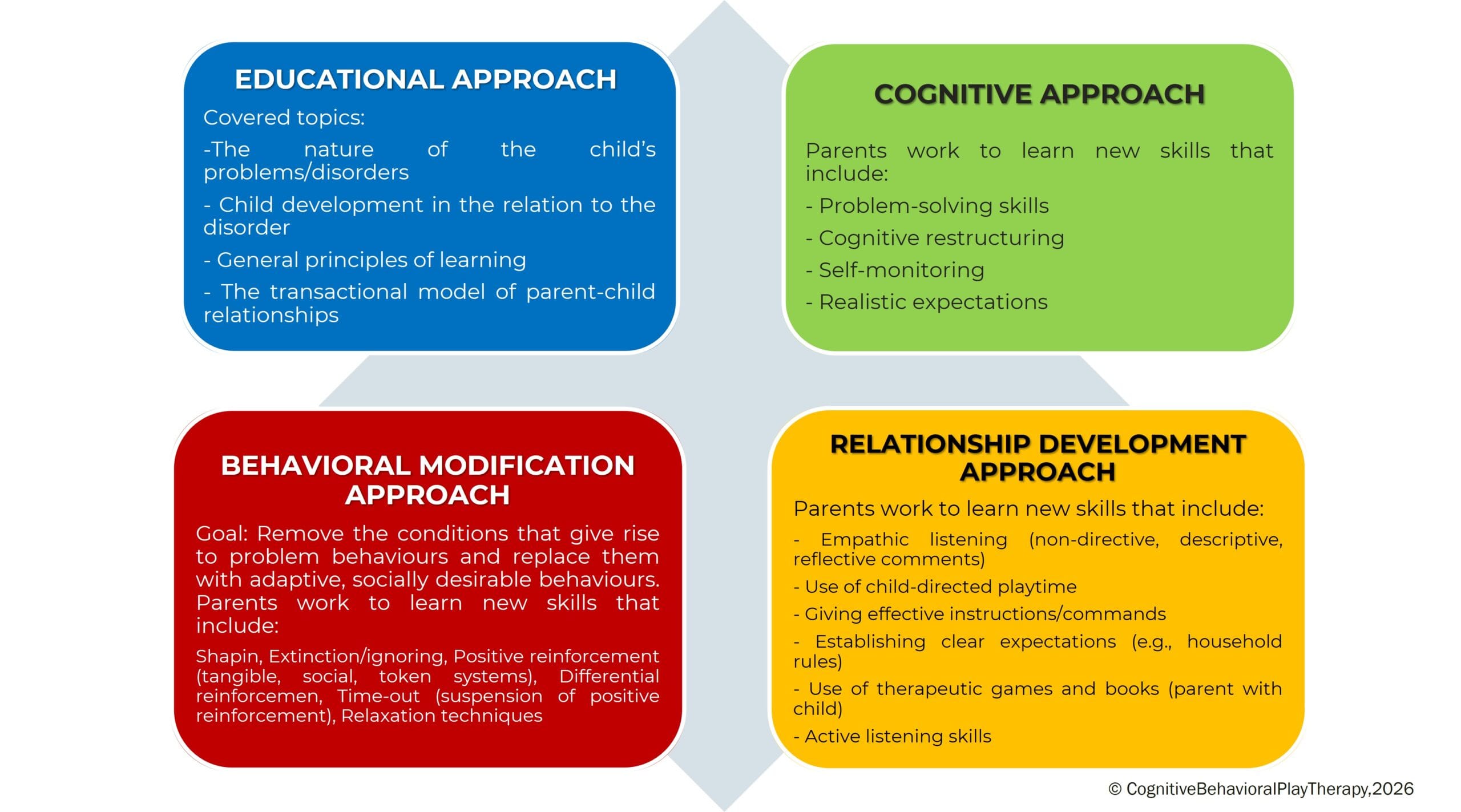

This program, called PARENT TRAINING CBPT, follows an integrated and innovative approach founded on the following frameworks:

Parent Training in Cognitive Behavioral Play Therapy

Although the primary work is with the child, it is important to meet periodically with the parents. Parental involvement in Cognitive Behavioral Play Therapy is essential both during assessment and throughout treatment. A parallel pathway to the child’s therapy is planned, emphasizing the fundamental role of parents in influencing their children’s maladaptive behaviors. Parents are often encouraged to strengthen and reinforce the child’s adaptive behavior so that treatment continues outside the therapy setting (for example, they are trained to use appropriate reinforcement for adaptive behaviors and extinction for maladaptive ones).

Target Population? Intended for both parents.

Duration? Typically 6 to 14 sessions, organized as one weekly session of 1 hour.

The program is structured into the following phases:

- ASSESSMENT PHASE: The problem is analyzed, parenting style is adapted, and therapeutic goals are defined. In this phase parents receive information about the causes and consequences of their children’s dysfunctional behaviors and learn to establish clear and consistent rules.

- LEARNING PHASE: This phase focuses on teaching new learnings of all the fundamental skills needed to support the child’s change. Parents have the opportunity to learn and practice techniques through practice sessions in which the therapist role-plays the child, guiding and instructing the parents. In particular, work focuses on:

- Mastery of prerequisites

- Modeling of skills

- Role-playing

- Errorless learning

- Successive approximations (shaping)

- Feedback (verbal and social reinforcers; token economy)

- Practice

- PRACTICE PHASE: In this phase parents conduct play sessions with their own children to put the learned skills into practice. Parents learn to recognize and prevent situations that trigger their children’s difficult behaviors and to use the same problem-solving strategies across different situations. After initial practice moments with the therapist, parents begin to run play sessions individually with their children under the therapist’s supervision.

- FEEDBACK AND GENERALIZATION PHASE:Parents discuss with the therapist the play sessions carried out at home to learn how to generalize what they have learned. Strengths and any problems that arose are reviewed. The therapist helps parents generalize all learned interventions and the parenting skills acquired during training. Each week some time is dedicated to applying techniques in everyday life, and homework assignments are given to practice the strategies.

- CONCLUSION PHASE: This phase occurs when therapeutic goals have been met and parents have achieved a satisfactory level of competence regarding play activities and parenting skills. Therapy is often tapered gradually, reducing session frequency to alternate weeks, then monthly, and so on.

Objectives of Parent Training

This program helps parents interact effectively with their child by developing functional behavioral and communicative habits and techniques. The intervention aims to remove conditions that give rise to problem behaviors and to replace them with adaptive and socially desirable conduct. Objectives focus on preventing dysfunctions, promoting well-being, and improving crisis conditions.

Specific objectives of working with parents include:

- Increase their understanding of the child’s problematic behaviour;

- Establish more realistic expectations;

- Increase warmth, trust, and acceptance toward the child.

- Understand the importance of interaction through play.

- Communicate more effectively with their children.

- Develop greater parental confidence and reduce frustrations experienced with their children.

- Develop greater patience to create more realistic expectations.

- Discuss personal reactions with the therapist to gain a deeper understanding of their own feelings and behaviours;

- Learn to become better problem solvers of family conflicts and develop stronger motivation for change.

Bibliography – References

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed.). Italian translation.

Berrini, R. (2021). La collaborazione psichiatra/psicologo sulla gestione integrata dei casi in psicoterapia individuale. Rivista semestrale di psicologia e psicoterapia individuale sistemica al tempo della complessità, 7.

Favaro, A., & Sambataro, F. (2021). Manuale di psichiatria. Piccin.

Geraci, M. A. (2022). La play therapy cognitivo-comportamentale. Armando Editore.

Geraci, M. A. (2023). Comprendere il mondo dei bambini giocando. Armando Editore.

Geraci, M. A. (2024). Il mondo della dottoressa Lulù. Collana Amzon – CBPT Books.

Knell, S. M. (1993). Cognitive Behavioral Play Therapy. J. Aronson.