GENERALIZED ANXIETY DISORDER (GAD): A COGNITIVE BEHAVIORAL PLAY THERAPY

What is Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD)?

Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD) falls within the diagnostic category of anxiety disorders. Anxiety disorders include conditions that share features of excessive fear and anxiety, along with related behavioral disturbances. These disorders differ from normal developmental fear or anxiety because they are excessive or persistent relative to the individual’s developmental stage. Children with generalized anxiety disorder may experience multiple and diffuse worries, which are intensified by stress. These children often have difficulty paying attention and may appear hyperactive and restless. They may sleep poorly, sweat excessively, feel fatigued, and report physical discomfort such as stomachaches, muscle tension, and headaches.

How does Generalized Anxiety Disorder manifest?

Generalized Anxiety Disorder is characterized by excessive anxiety and worry occurring more days than not for at least 6 months, concerning a number of events or activities, including school or work performance. Children tend to worry excessively about their abilities or academic performance. Over the course of the disorder, the focus of worry may shift from one topic to another. Additionally, children may appear excessively perfectionistic (redoing tasks they do not consider sufficiently perfect) and insecure (seeking constant reassurance about their performance and the things they worry about).

Anxiety and worry are associated with the following symptoms:

- Restlessness or feeling on edge

- Easy fatigability

- Difficulty concentrating

- Irritability

- Muscle tension

- Sleep disturbances (difficulty falling or staying asleep, or restless and unsatisfying sleep)

The intensity, duration, or frequency of anxiety and worry are excessive compared to the actual likelihood or impact of the feared event. Moreover, the individual struggles to control the worry and to prevent anxious thoughts from interfering with attention to ongoing tasks.

When does Generalized Anxiety Disorder appear?

Specific manifestations of anxiety vary across developmental stages. It is always important to differentiate normal or adaptive anxiety from pathological anxiety. Anxiety is an emotional and physiological state present from birth; at appropriate levels, it has an important adaptive function and can enhance a child’s resources and abilities. However, high levels of anxiety may become pathological and lead to clinical anxiety disorders. In childhood, the average age of onset is around 12 years, and the disorder occurs more frequently in females than males, with a ratio of approximately 2:1. Since individuals with anxiety disorders tend to overestimate danger in feared or avoided situations, the primary evaluation of whether fear or anxiety is excessive is made by the clinician, who considers cultural and contextual factors. It is essential that anxiety disorders arising in childhood be addressed by a clinician, as they may persist and become chronic.

What causes Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD)?

Several factors contribute to the development of generalized anxiety disorder:

- Temperamental factors: behavioral inhibition, negative affectivity, and harm avoidance have been associated with GAD.

- Environmental factors: although childhood adversities and parental overprotectiveness have been linked to GAD, no specific environmental factors have been identified as necessary or sufficient for diagnosis.

- Genetic and physiological factors: about one-third of the risk for GAD is genetic. These genetic factors overlap with the risk for neuroticism and are shared with other anxiety and mood disorders.

Generalized Anxiety Disorder and Cognitive Behavioral Play Therapy (CBPT)

The Cognitive Behavioral Play Therapy (CBPT) approach aims to influence mood by first modifying behaviors and thought patterns.

When anxiety and fear interventions incorporate play, children become more engaged. In a literature review, Augustyn and Hermann (2017) state that “fears can often be managed through reassurance, education, experience, and/or exploration through play (e.g., games involving monsters, scary animals, or ghosts)” (p. 7).

The goal of CBPT with anxious children is to help them manage their fears and return to a state of emotional, behavioral, cognitive, and physical well-being.

CBPT is a structured, brief, and goal-oriented therapy in which goals are shared with the child and family. The child is welcomed into a play setting designed to build the therapeutic alliance, while parents follow a parallel path aimed at learning and strengthening parenting skills.

Phases of the Intervention:

- ORIENTATION PHASE: This is the initial phase of cognitive-behavioral play therapy. Significant emphasis is placed on preparing both the child and the parents. It is crucial to organize an initial meeting between the therapist and the parents—without the child—to thoroughly review history and background information. This allows parents to share their perception of the child’s difficulties. During these initial meetings, the therapist helps parents prepare the child for the first session. The ongoing role of parents and other significant adults in the assessment and treatment process is also explained. Although the focus is on the child during CBPT sessions, the therapist continues to interact regularly with parents to provide support and evaluate progress toward therapeutic goals.

- ASSESSMENT PHASE: This phase focuses on gathering essential information to establish therapy goals. In addition to parent interviews, a key component is observing the child’s play. Various tools are used, including parent questionnaires, child play assessment, family play assessment, puppet-based sentence completion tasks, and other therapist-developed measures. The therapist may establish a baseline for the frequency of the child’s behaviors, allowing for evaluation of changes throughout treatment.

- CASE CONCEPTUALIZATION PHASE: CBPT begins with analyzing the data collected during the child’s assessment to plan an effective treatment and provide a logical structure for developing and achieving therapeutic goals. This phase includes explaining GAD, analyzing individual, relational, and environmental factors related to the child’s worries, and examining emotions, thoughts, physical sensations, and coping strategies used by the child. Protective, risk, and maintaining factors contributing to the child’s behavior are also explored.

- INTERVENTION PHASE: This phase focuses on using CBT techniques to help the child with GAD develop more adaptive responses to problems, situations, and stressors. The emphasis is on learning more adaptive thoughts and behaviors. Methods include modeling, role-playing, bibliotherapy, generalization, and relapse prevention. Interventions often consist of traditional cognitive strategies adapted through play tools such as drawing and expressive arts, therapeutic storytelling, or puppet interactions involving characters facing similar situations. Treatment includes helping the child generalize learned behaviors to other contexts and working on relapse prevention. Although the primary focus is the child, regular meetings with parents remain essential to monitor progress, evaluate parent–child interactions, and provide guidance on relevant areas.

- CONCLUSION PHASE: Both the child and the family are actively involved in this final phase. The child addresses feelings related to the end of therapy, while the therapist highlights changes and consolidates learning. Final sessions may be spaced out—from weekly to biweekly or monthly—to help the child perceive their ability to manage life without the therapist. The therapist reinforces progress between sessions and normalizes the experience of separation. Follow-ups at 3, 6, 12, and 24 months are planned to assess the intervention’s effectiveness.

What are Therapeutic Goals?

In CBPT, goals are defined collaboratively with children and their families. In the context of Generalized Anxiety Disorder, the following goals are typically pursued:

- Facilitating emotional expression and regulation

- Reducing symptoms and problematic behaviors

- Developing new coping skills and strategies

- Strengthening resources and personal strengths

- Enhancing problem-solving abilities

- Providing psychoeducation to both parents and child

CBPT can be particularly suitable for children with generalized anxiety because it allows them to:

- Actively participate in the change process

- Experience a sense of mastery

- Maintain control over communication

- Learn more adaptive responses

What can Parents do?

It is important for parents to:

- Be patient and support the child without pressure

- Collaborate with therapists and teachers to create a supportive environment

ENHANCE YOUR CHILD PSYCOTHERAPY SKILLS

COGNITIVE BEHAVIORAL PLAY THERAPY TRAINING

Parent Training in Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD)

What is Parent Training?

Parent Training is a competence-based intervention model grounded in the assumption that families are capable of managing and addressing the child’s difficulties, and that all families possess strengths and can learn new skills.

Within Cognitive Behavioral Play Therapy, parent training emphasizes the importance of involving parents directly in the playroom setting. Parents are given the opportunity to observe and gradually implement interventions aimed at modeling adaptive behaviors in the presence of the therapist. This approach highlights parents’ capacity for adaptation and learning, and encourages modifications in relational styles and attitudes that may negatively influence children’s behaviors.

Through this process, parents have the opportunity to:

- Acquire new skills

- Learn and practice specific techniques

- Receive individualized and continuous feedback from the therapist to enhance their awareness

- Learn to interpret more accurately their child’s emotions, worries, and communication as expressed through play

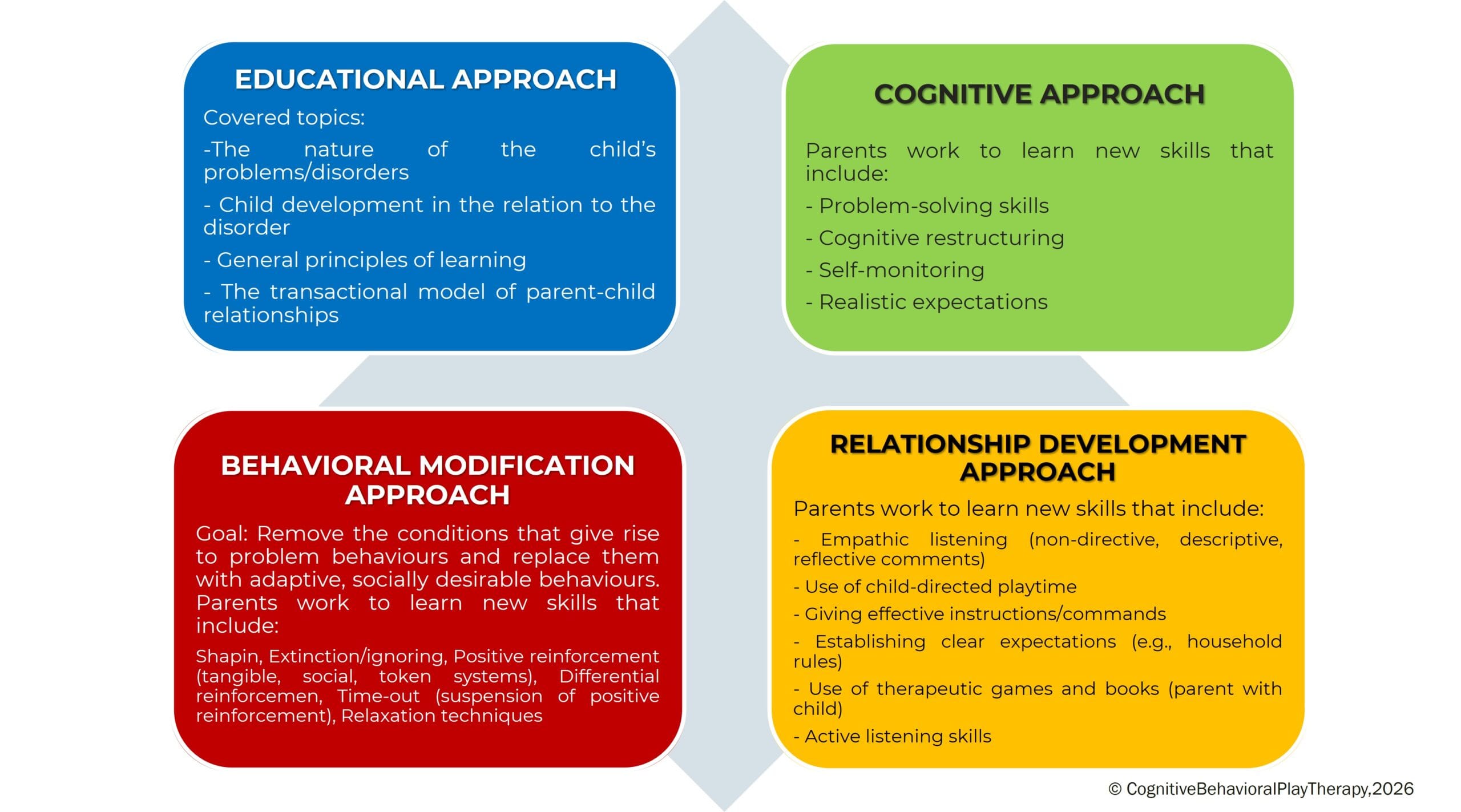

This program, referred to as CBPT Parent Training, follows an integrated and innovative approach based on the following principles:

How is Parent Training structured in Cognitive Behavioral Play Therapy?

Although the primary work is conducted with the child, it is essential to meet periodically with the parents as well. Parental involvement in Cognitive Behavioral Play Therapy is crucial during both the assessment and treatment phases. A parallel path to the child’s therapy is planned, emphasizing the fundamental role parents play in influencing their child’s maladaptive behaviors. Parents are often encouraged to strengthen and reinforce the child’s adaptive behaviors to support treatment outside the therapy setting (e.g., they are trained to use appropriate reinforcement for adaptive behaviors and extinction procedures for maladaptive ones).

Who is it for? It is intended for both parents.

How long does it last? Typically, the program consists of 6 to 14 sessions, held once a week, each lasting one hour.

The Program is structured into phases

- ASSESSMENT PHASE: The problem is analyzed, the parenting style is adjusted, and goals are defined. During this phase, parents receive information about the causes and consequences of their child’s dysfunctional behaviors and learn to establish clear and consistent rules.

- LEARNING PHASE: This phase focuses on developing new skills essential to supporting the child’s change. Parents have the opportunity to learn and practice specific “techniques” through practice sessions in which the therapist takes on the role of the child, guiding and instructing the parents.

Key areas of work include:

- Mastery of prerequisite skills

- Skill modeling

- Role-playing

- Errorless learning

- Successive approximations (shaping)

- Feedback (verbal and social reinforcers, token economy)

- Practice

- PRACTICE PHASE: In this phase, play sessions with their children are introduced. Parents apply the skills they have learned. They learn to recognize and prevent situations that trigger difficult behaviors and to use the same problem-solving strategies across different contexts. After initial practice moments with the therapist, parents begin conducting individual play sessions with their children under the therapist’s supervision.

- REVIEW AND FEEDBACK PHASE: Parents discuss with the therapist the play sessions conducted at home to learn how to generalize what they have learned. They review what they feel they did well and address any difficulties that emerged. During this phase, the therapist helps parents generalize all the interventions and foundational skills they acquired during training. Each week, time is dedicated to applying what they have learned in daily life situations, and homework assignments are given to encourage the use of the techniques.

- CONCLUSION PHASE: This phase occurs when therapeutic goals have been achieved and parents have acquired a solid level of competence in both play activities and parenting skills. Therapy is often concluded gradually, with sessions shifting from weekly to biweekly, then monthly, and so on.

Goals of Parent Training

This program helps parents interact effectively with their child by developing functional behavioral and communication habits and techniques. The goal of the intervention is to remove the conditions underlying problem behaviors and replace them with adaptive and socially desirable behaviors. The objectives focus on preventing dysfunction, promoting well-being, and improving crisis situations.

Specific goals of working with parents include:

- Increasing their understanding of the child’s problematic behavior

- Establishing more realistic expectations

- Enhancing warmth, trust, and acceptance toward the child

- Understanding the importance of interaction through play

- Communicating more effectively with their children

- Developing greater confidence as parents and reducing frustration

- Building greater patience to create more realistic expectations

- Discussing personal reactions with the therapist to better understand their own feelings and behaviors

- Learning how to become effective problem-solvers and manage family conflicts

- Increasing motivation toward change

References

American Psychiatric Association (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders – Fifth Edition (DSM-5).

Berrini, R. (2021). La collaborazione psichiatra/psicologo sulla gestione integrata dei casi in psicoterapia individuale. Rivista semestrale di psicologia e psicoterapia individuale sistemica al tempo della complessità, 7.

Favaro, A., & Sambataro, F. (2021). Manuale di psichiatria. Piccin.

Geraci, M. A. (2022). La play therapy cognitivo-comportamentale. Armando Editore.

Geraci, M. A. (2023). Comprendere il mondo dei bambini giocando. Armando Editore.

Geraci, M. A. (2024). Il mondo della dottoressa Lulù. Collana Amazon – CBPT Books.

Knell, S. M. (1993). Cognitive Behavioral Play Therapy. J. Aronson.