ADHD: COGNITIVE BEHAVIORAL PLAY THERAPY

What is ADHD (Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder)?

Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) is a neurodevelopmental disorder of childhood and adolescence characterized by a persistent pattern of inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity that interferes with functioning or development. In child neuropsychiatry it is one of the most frequently diagnosed disorders. It is pervasive and chronic, typically appears before age 7, and is more commonly observed in males. Although commonly associated with childhood, ADHD can persist into adulthood and cause significant impacts on daily life and interpersonal relationships.

People with ADHD may have difficulty concentrating on specific tasks or activities, for example following instructions, organizing activities, or completing school or work tasks. They may also be hyperactive, showing excessive motor restlessness, or impulsive, acting without considering consequences.

ADHD varies in severity and presentation from person to person. Some individuals may be primarily inattentive, others primarily hyperactive-impulsive, and some may show symptoms of all three presentations, known as combined ADHD.

Main types of ADHD:

- Predominantly Inattentive ADHD: Characterized by difficulty maintaining attention on specific tasks or activities. Children with this presentation may appear “lost in thought” and may have trouble completing tasks or following instructions.

- Predominantly Hyperactive-Impulsive ADHD: Manifests with excessive energy and difficulty remaining still or seated for long periods. Children with this presentation may seem constantly in motion and have trouble controlling impulses, acting without reflecting on consequences.

- Combined ADHD: Includes symptoms of both inattention and hyperactivity/impulsivity. This is the most common type of ADHD.

How ADHD manifests?

Childhood ADHD can present in different ways, and symptoms vary from child to child. Below are common ways ADHD may manifest in children:

- Inattention: Children with ADHD may have difficulty concentrating on specific tasks or activities. They may appear distracted, often missing important details or making careless mistakes in schoolwork or daily activities. They may have trouble following instructions, maintaining attention during conversations, or completing tasks. In school this appears as clear difficulty attending to details, “careless errors,” and incomplete or messy work. Teachers report that children with ADHD seem not to listen and are easily distracted by sounds or other irrelevant stimuli.

In general, outside the school environment as well, a person with ADHD in the domain of attention often:

- often fails to pay attention to details or make careless mistakes in schoolwork, at work, or in other activities.

- often has difficulty sustaining attention on tasks or play activities.

- often does not seem to listen when spoken to directly.

- often does not follow through on instructions and fails to finish schoolwork, chores, or duties at work (not due to oppositional behavior or inability to understand instructions);

- often has difficulty organizing tasks and activities.

- often avoids, dislikes, or is reluctant to engage in tasks requiring sustained mental effort (e.g., schoolwork or homework);

- often loses items necessary for tasks or activities (e.g., toys, school assignments, pencils, books, or tools);

- is often easily distracted by extraneous stimuli, often forgetful in daily activities.

- Hyperactivity: Some children with ADHD may be hyperactive, meaning they have excess energy and movement. They may seem constantly on the go, run or fidget inappropriately when calm is expected. They may have difficulty remaining seated during lessons or meals and may appear always in action. Hyperactivity can be both motor (running around, unable to stay still or seated) and vocal.

Common signs include:

- often fidgets with hands or feet or cannot stay seated.

- gets up in class or in situations where remaining seated is expected.

- runs about or climbs excessively when such activities are inappropriate.

- has difficulty playing quietly.

- seems constantly “on the go” as if driven by a motor.

- talks excessively.

- Impulsivity: Impulsivity involves difficulty controlling impulses. Children may interrupt others during conversations, act without thinking about consequences, or engage in risky behaviors. They may have difficulty waiting their turn in group situations or following rules. Impulsivity can be cognitive (e.g., not respecting conversational turns) or physical (e.g., undertaking dangerous actions without considering negative consequences, such as crossing a street without checking for traffic). A core feature is an inability to wait. Impulsivity tends to remain relatively stable across development (though it takes different forms with age) and is often present in adults with ADHD as well.

In general, a person with ADHD in the domain of impulsivity often:

- answers before questions have been completed.

- has difficulty waiting their turn.

- often interrupts or intrudes on others (e.g., butts into conversations or games).

- Disorganization: ADHD can cause difficulties organizing daily activities and tasks. Children may regularly lose important items, forget to complete assignments, or struggle to follow a routine.

- Difficulties in interpersonal relationships Children with ADHD may have trouble making friends or maintaining positive social relationships. They may have problems understanding others’ emotions or responding appropriately in social situations.

Not all children with ADHD display all of these symptoms, and symptom severity ranges from mild to severe. Symptoms can change over time; some may improve with age or with appropriate treatment. Diagnosis and treatment of childhood ADHD require individualized, personalized attention from qualified professionals.

When ADHD Manifests?

In children aged 12 to 16 years, most studies report prevalence rates ranging from 2% to 6%. ADHD in young children tends to be relatively persistent over time. Symptom stability increases with the child’s age: therefore, symptom stability in the preschool period will be greater than in early childhood but lower than in school age.

What Causes ADHD (Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder)?

Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder does not have a single specific cause. The origin of the disorder appears to depend on the interaction of multiple environmental, social, behavioral, biochemical, and genetic factors.

Genetic studies involving children have shown associations between ADHD and certain genes. For example, an alteration in a gene involved in the production of neurotransmitter dopamine could be one of the causes of the disorder. Dopamine transmits information between neurons and underlies many cognitive processes such as attention and memory. Although consistent scientific evidence is still limited, most medications used to treat ADHD act with the aim of enhancing dopamine activity, thereby helping the individual to sustain attention.

Further studies have also demonstrated familial aggregation: a child with ADHD is four times more likely to have a relative with the same condition.

There are also environmental risk factors, particularly prenatal and perinatal factors, associated with ADHD, such as:

- prolonged exposure to tobacco smoke.

- alcohol or drug use during pregnancy.

- Hypertension.

- Stress.

- complications during delivery.

- preterm birth.

- low birth weight.

- Exposure to environmental toxins increases the risk of behavioral and developmental problems. Exposure to lead, commonly found in paints and pipes of older buildings, has been linked to destructive and even violent behaviors and to reduced concentration capacity.

- Food additives (artificial colorings and preservatives) may contribute to hyperactive behavior.

Conflicted interactions between parents and the child also play an important role, potentially increasing the likelihood that the disorder will fully manifest and reach greater severity.

Neurobiological causes that may underline ADHD include deficits in the structure and function of the frontal brain regions, which are responsible for primary cognitive processes such as planning and organizing behavior, attention, and inhibitory control. Structural deficits may also affect brain regions that regulate emotions and parts of the nervous system that mediate communication within the brain.

All these brain regions are interconnected, therefore, a deficit in even one of them could give rise to the disorder.

ADHD and Cognitive Behavioral Play Therapy

The ideal treatment for ADHD is multimodal, meaning it involves the school, the family, and the child, and includes pharmacological intervention where and when necessary. Currently, ADHD is typically treated with a combination of medication and behavioral therapy.

In particular, Cognitive Behavioral Play Therapy (CBPT) has grown over the past 20 years and is increasingly used as a treatment of choice for children. Play is their language, and during a play therapy session children are free and open to learning. Cognitive behavioral play therapy can incorporate standard cognitive and behavioral techniques in a fun, non-threatening format. Because interventions are engaging and playful, children with ADHD adapt to and participate in their treatment.

The therapeutic powers of play—such as facilitating communication, self-regulation, and both direct and indirect teaching (Schaefer & Drewes, 2014)—can help children with ADHD identify and communicate their difficulties through play and engage more fully in treatment. A vital aspect of using play therapy is that the child is actively involved, practices skills, and develops the competencies required by the intervention.

Cognitive-behavioral treatment has been shown to produce positive outcomes for children with ADHD (Antshel et al., 2014; Harris et al., 2005; Kaduson, 1997b; Raggi & Chronis, 2006). Cognitive behavioral play therapy, however, adds the important element of play to tasks and techniques (Abdollahian et al., 2013; Kaduson, 1997a).

The pleasure and positive sensations of play allow children with ADHD to experience more positive feelings that counteract the negative impact of teachers, parents, siblings, and peers telling them to stop, pay attention, and behave (Kaduson, 1997b).

Children with ADHD tend not to complete tasks and may shift from one activity to another, but during a play period they can stick to a task with the therapist’s help and experience a sense of accomplishment. Finally, play has a “as if” quality: children enact play as if it were real life. This is extremely advantageous for children with ADHD because they can solve problems, make mistakes, try solutions, all without the critical gaze of others.

Cognitive behavioral play therapy is a structured, brief, goal-oriented therapy whose goals are shared with the child and the family. The child is welcomed into a play setting designed to build the therapeutic alliance, while parents follow a parallel pathway aimed at learning and strengthening parenting skills.

Intervention Phases:

- Orientation Phase: This is the initial phase of cognitive-behavioral play therapy. There is significant emphasis on preparing both the child and the parents. It is crucial to arrange an initial meeting between the therapist and the parents, without the child present, to review history and background information in detail. This allows parents to share their perception of the child’s problem. During these initial meetings the therapist helps parents prepare the child for the first session. The ongoing role of parents and other significant adults in the child’s assessment and treatment process is also explained. Although the focus is on the child during CBPT, the therapist continues to interact regularly with parents to provide support and evaluate progress toward therapeutic goals.

- Assessment Phase: This phase focuses on gathering crucial information to establish therapy goals. In addition to interviews with parents, a key element is observation of the child’s play. Various instruments are used during this phase, including parent questionnaires, assessment of the child’s play, assessment of family play, a puppet sentence-completion task, and other measures tailored by the therapist. The therapist can establish a baseline for the frequency of the child’s behaviors, allowing measurement of behavioral change over the course of treatment.

- Case Conceptualization Phase: CBPT begins with analysis of the data collected during assessment to plan an effective treatment and provide a logical framework for developing and achieving therapeutic goals. The process starts with an explanation of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), analyzing individual, relational, and environmental factors related to parents’ concerns. The child’s emotional experience, thoughts, physical sensations, and coping strategies are examined. This phase also includes analysis of protectiveness, risk, and maintaining factors that contribute to the child’s behavior.

- Intervention Phase: The therapy phase in CBPT focuses on using CBT techniques that help the child with ADHD develop more adaptive responses to problems, situations, and stressors. The emphasis is on learning more adaptive thoughts and behaviors. Methods include modeling, role-playing, bibliotherapy, generalization, and relapse prevention. Interventions often adapt traditional cognitive techniques through play tools such as drawing and expressive arts, listening to stories with therapeutic storytelling, or interacting with puppets that face similar situations. Treatment includes interventions to help the child generalize behaviors learned in sessions to other contexts and to work on relapse prevention. Although the primary focus is the child, it is important to maintain regular meetings with parents to monitor progress, assess and intervene in parent–child interactions, and provide guidance on target areas.

- Termination Phase: Both the child and the family are actively involved in termination. During this final period the child addresses feelings related to ending therapy while the therapist highlights change and consolidates the learning process. Final sessions may be spaced out over time, moving from weekly to biweekly or monthly meetings. This helps the child perceive their ability to manage life without the therapist. The therapist positively reinforces the child’s progress between sessions and seeks to normalize the separation experience. Follow-ups are scheduled at 3, 6, 12, and 24 months after the end of the intervention to verify its effectiveness.

Therapeutic Goals?

In CBPT the definition of goals is shared with children and their families. In the context of ADHD, typical goals include:

- Developing strategies that systematically guide the child in planning their behavior across life domains and in problem solving.

- Acquiring the ability to monitor one’s actions, developing self-regulation to reduce impulsivity and inattention.

- Learning from errors to self-correct and to reward oneself for achieving positive outcomes.

- Increasing social skills, through rule-following, developing more effective interactions, and improving the ability to decode others’ emotional states to respond and relate appropriately and functionally.

What Parents Can Do?

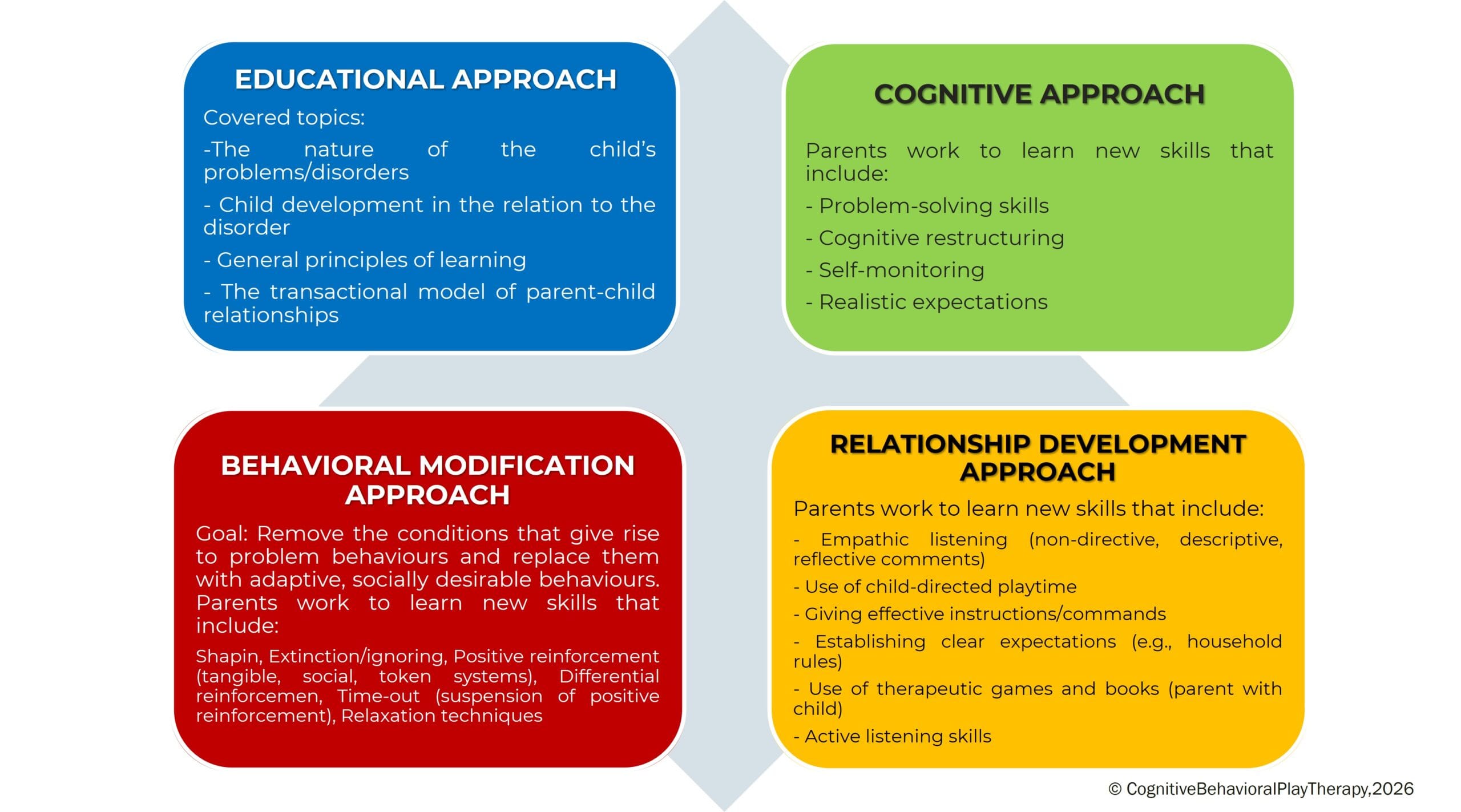

To facilitate the intervention, parents should be trained in understanding and managing their child’s behavior and in how to be the supporters the child needs. A multimodal approach also includes parent training regarding the facts of ADHD diagnosis and treatment.

ENHANCE YOUR CHILD PSYCOTHERAPY SKILLS

COGNITIVE BEHAVIORAL PLAY THERAPY TRAINING

Parent Training in ADHD (Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder)

What is Parent Training?

Parent Training is a competency-based intervention model that starts from the assumption that families are capable of managing and addressing the problem, and that all families have strengths and can learn.

Parent training integrated into Cognitive Behavioral Play Therapy emphasizes the importance of involving parents in the playroom setting as well. Parents can observe and progressively implement interventions to shape adaptive behaviours in the presence of the therapist. It highlights parents’ capacity to adapt and to learn, and proposes modifying relational styles and attitudes that negatively influence children’s behaviours.

In this way, parents have the opportunity to:

- Learn new skills

- Learn and practice specific techniques

- Receive individualized, ongoing feedback from the therapist to help them become more aware

- Learn to interpret more accurately their children’s emotions, concerns, and communication as expressed through play

This program, called PARENT TRAINING CBPT, follows an integrated and innovative approach found on the following methods:

How is the Parent Training structured in Cognitive Behavioral Play Therapy?

Although the primary work is with the child, it is important to meet periodically with the parents. Parental involvement in Cognitive Behavioral Play Therapy is essential both during assessment and throughout treatment. A parallel pathway to the child’s therapy is provided, emphasizing the fundamental role of parents in influencing their children’s maladaptive behaviours. Parents are often encouraged to reinforce adaptive child behaviour to continue the treatment outside the therapy setting (e.g., they are trained to use appropriate reinforcement for adaptive behaviours and extinction for maladaptive ones).

- Target? Intended for both parents.

- Typical duration? Generally, 6 to 14 sessions, organized as one 1-hour session per week.

The Program is structured in phases

- ASSESSMENT PHASE The problem is analysed, the parenting style is adapted, and the treatment goal is defined. In this phase parents receive information about the causes and consequences of their children’s dysfunctional behaviours and learn to establish clear and consistent rules.

- LEARNING PHASE This phase focuses on defining new learnings of all the fundamental skills needed to support the child’s change. Parents have the opportunity to learn and practise the “techniques” through guided practice sessions in which the therapist role-plays the child, guiding and instructing the parents. In particular, work focuses on:

- Mastery of prerequisites;

- Modelling of skills;

- Role-playing;

- Errorless learning;

- Successive approximations (shaping);

- Feedback (verbal and social reinforcers, token economy);

- Practice.

- PRACTICE PHASE This phase includes play sessions with their own children to put the learned skills into practice. Parents learn to recognise and prevent situations that trigger their children’s difficult behaviours and to use the same problem-solving strategies across different situations. After initial practice moments with the therapist, parents begin to run individual play sessions with their children under the therapist’s supervision.

- REVIEW / GENERALIZATION PHASE Parents discuss home play sessions with the therapist to learn how to generalize what they have learned. The aspects parents feel they performed well are reviewed and any problems that arose are addressed. In this phase the therapist helps parents generalize all learned interventions and the parenting skills acquired during training. Each week some time is dedicated to applying what has been learned in everyday life situations and homework assignments are given to practise the techniques.

- TERMINATION PHASE Termination occurs when therapeutic goals have been achieved and parents have acquired a good level of competence regarding play activities and parenting skills. Therapy is often concluded gradually, with session frequency reduced to alternate weeks, then monthly, and so on.

Objectives of Parent Training

This program helps parents interact effectively with their child by developing functional behavioural and communicative habits and techniques. The aim of the intervention is to remove the conditions that give rise to problem behaviours and to replace them with adaptive and socially desirable behaviours. Objectives are focused on preventing dysfunction, promoting well-being, and improving crisis conditions.

Specific objectives of working with parents include:

- Increase their understanding of the child’s problematic behaviour;

- Establish more realistic expectations;

- Increase warmth, trust, and acceptance toward the child.

- Understand the importance of interaction through play.

- Communicate more effectively with their children.

- Develop greater parental confidence and reduce frustrations experienced with their children.

- Develop greater patience to create more realistic expectations.

- Discuss personal reactions with the therapist to gain a deeper understanding of their own feelings and behaviours;

- Learn to become better problem solvers of family conflicts and develop stronger motivation for change.

Bibliography

- American Psychiatric Association (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders — Fifth Edition (DSM-5). Italian translation.

- Abdollahian, E., Mokhber, N., Balaghi, A., & Moharrari, F. (2013). The effectiveness of cognitive-behavioral play therapy on the symptoms of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children aged 7–9 years. ADHD Attention Deficit and Hyperactivity Disorders, 5(1), 41–46.

- Antshel, K. M., Faraone, S. V., & Gordon, M. (2012). Cognitive Behavioral Treatment Outcomes in Adolescent ADHD. Journal of Attention Disorders, 18(6), 483-495.

- Favaro, A., & Sambataro, F. (2021). Manuale di psichiatria. Piccin.

- Geraci, M. A. (2022). La play therapy cognitivo-comportamentale. Armando Editore.

- Geraci, M. A. (2023). Comprendere il mondo dei bambini giocando. Armando Editore.

- Geraci, M. A. (2024). Il mondo della dottoressa Lulù. CBPT Books (Amazon series).

- Harris, K. R., Danoff Friedlander, B., Saddler, B., Frizzelle, R., & Graham, S. (2005). Self-Monitoring of Attention Versus Self-Monitoring of Academic Performance: Effects Among Students with ADHD in the General Education Classroom: Effects Among Students with ADHD in the General Education Classroom. The Journal of Special Education, 39(3), 145-157.

- Kaduson, H. G., Cangelosi, D., & Schaefer, C. E. (Eds.). (1997). The playing cure: Individualized play therapy for specific childhood problems. Jason Aronson.

- Knell, S. M. (1993). Cognitive Behavioral Play Therapy. J. Aronson.

- Pandolfi, E. (2010). I Disturbi Esternalizzanti nell’Infanzia: fattori di rischio e traiettorie di sviluppo. Semestrale, School of Specialization in Cognitive Psychotherapy and Association of Cognitive Psychology, 50.

- Raggi, V.L., Chronis, A.M. Interventions to Address the Academic Impairment of Children and Adolescents with ADHD. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev 9, 85–111 (2006).

- Schaefer, C. E., & Drewes, A. A. (Eds.). (2013). The therapeutic powers of play: 20 core agents of change (2nd ed.). John Wiley & Sons.