Oppositional Defiant Disorder: Cognitive Behavioral Play Therapy

What is Oppositional Defiant Disorder?

Oppositional Defiant Disorder (ODD) falls within the diagnostic category of disruptive behavior disorders, impulse-control disorders, and conduct disorders, which include conditions involving difficulties in self-control of emotions and behaviors. It is typical of childhood and is characterized by a stable and prolonged irritable mood, provocative, hostile and argumentative behaviors toward authority figures, and an inability to take responsibility for one’s actions and mistakes.

How is the Oppositional Defiant Disorder present?

ODD is marked by a recurrent and persistent pattern of defiance, disobedience, and hostility toward authority figures (parents, teachers, and other adults). The core feature is a frequent and persistent pattern of angry/irritable mood, argumentative/defiant behavior, or vindictiveness lasting at least six months, demonstrated by the presence of at least four of the following symptoms:

- often loses temper;

- is touchy or easily annoyed;

- is often angry and resentful;

- often argues with authority figures (parents, teachers) or with adults;

- often actively defies or refuses to comply with requests from authority figures or with rules;

- is spiteful or vindictive.

Symptoms are more evident in interactions with adults and often lead to significant impairment in school and interpersonal functioning.

When does ODD appears?

Early signs of Oppositional Defiant Disorder can be identified as early as ages 5–6, although many children receive an ODD diagnosis in preadolescence. Oppositional symptoms often emerge in the family environment but may later appear in other contexts. Early intervention is important because, as literature shows, in some cases the disorder can worsen during puberty or adolescence and progress to Conduct Disorder.

Causes of Oppositional Defiant Disorder?

Contributing factors may include:

- Environmental factors: rigid, inconsistent, or neglectful parenting practices are common in families of children and adolescents with ODD and play an important role in many etiological theories.

- Temperamental factors: temperament traits related to emotional regulation problems, such as high emotional reactivity and low frustration tolerance, predict the disorder.

- Genetic and physiological factors: several neurobiological markers—such as low resting heart rate, altered skin conductance reactivity, reduced basal cortical reactivity, and anomalies in the prefrontal cortex and amygdala—may be associated with ODD.

Cognitive Behavioral Play Therapy for Oppositional Defiant Disorder

The ideal treatment involves the engagement of school, family, and the child, and includes pharmacological intervention when necessary.

Cognitive Behavioral Play Therapy (CBPT) has expanded over the last 20 years and is increasingly used as a firstline treatment for children. Play is the child’s language; during play therapy sessions children are free and open to learning. CBPT can incorporate standard cognitive and behavioral techniques in a fun, non-threatening format. Because interventions are engaging and playful, children are more likely to cooperate and participate in treatment.

Therapeutic aspects of plays such as facilitating communication, self-regulation, and direct and indirect teaching (Schaefer & Drewes, 2014) help children identify and communicate their problems through play and engage more fully in treatment. A vital element of play therapy is that the child is actively involved, practices skills, and develops the competencies targeted by treatment.

Evidence shows that cognitive-behavioral treatment can yield positive outcomes (Antshel et al., 2014; Harris et al., 2005; Kaduson, 1997b; Raggi & Chronis, 2006). CBPT adds the important element of play to tasks and techniques (Abdollahian et al., 2013; Kaduson, 1997a), allowing positive feelings from play to counteract negative impacts from teachers, parents, siblings, and peers who tell the child to stop, pay attention, or behave (Kaduson, 1997b).

CBPT is a structured, brief, goal-oriented therapy whose objectives are shared with the child and family. The child is welcomed into a play setting designed to build the therapeutic alliance, while parents follow a parallel pathway aimed at learning and strengthening parenting competencies.

Intervention Phases:

- Orientation Phase: This initial phase emphasizes preparing both the child and the parents. It is crucial to schedule an initial meeting between the therapist and the parents, without the child present, to review history and background information in detail. This allows parents to share their perception of the child’s problem. During these meetings the therapist helps parents prepare the child for the first session and explains the ongoing role of parents and other significant adults in assessment and treatment. Although the focus is on the child during CBPT, the therapist continues to interact regularly with parents to provide support and evaluate progress toward therapeutic goals.

- Assessment Phase: This phase focuses on collecting essential information to establish therapy goals. In addition to parent interviews, a key element is observation of the child’s play. Tools used may include parent questionnaires, assessment of the child’s play, family play assessment, a sentence-completion task with puppets, and other measures personalized by the therapist. The therapist may establish a baseline for the frequency of the child’s behaviors to evaluate behavioral changes over the course of treatment.

- Case Conceptualization Phase: CBPT begins with analysis of the data collected during assessment to plan an effective treatment and provide a logical framework for developing and achieving therapeutic goals. The process starts by explaining Oppositional Defiant Disorder and analyzing individual, relational, and environmental factors related to parents’ concerns. The child’s emotions, thoughts, physical sensations, and coping strategies are examined. This phase also includes analysis of protective, risk, and maintaining factors that contribute to the child’s behavior.

- Intervention Phase: The intervention phase focuses on using CBT techniques to help the child with ODD develop more adaptive responses to problems, situations, and stressors. Emphasis is placed on learning more adaptive thoughts and behaviors. Methods include modeling, role-playing, bibliotherapy, generalization, and relapse prevention. Interventions often adapt traditional cognitive techniques through play tools such as drawing and expressive arts, therapeutic storytelling, or interaction with puppets facing similar situations. Treatment includes strategies to help the child generalize skills learned in sessions to other contexts and to work on relapse prevention. Although the primary focus is on the child, regular meetings with parents are important to monitor progress, assess and intervene in parent–child interactions, and provide guidance on areas of concern.

- Conclusion Phase: Both the child and the family are actively involved in the final phase. During this period the child processes feelings related to the end of therapy while the therapist highlights changes and consolidates learning. Final sessions may be spaced out over time, moving from weekly to biweekly or monthly meetings, helping the child perceive their ability to cope without the therapist. The therapist reinforces the child’s progress between sessions and normalizes the separation experience. Follow-ups are scheduled at 3, 6, 12, and 24 months after the intervention to verify effectiveness.

Therapeutic Goals?

In CBPT, goals are defined collaboratively with children and their families. For ODD, common objectives include:

- develop strategies that systematically guide the child to plan behavior across life domains and solve problems (problem solving);

- acquire the ability to monitor actions and develop self-regulation to reduce impulsivity and inattention;

- learn to extract useful information from mistakes for self-correction and to reward oneself for positive achievements;

- increase social skills through rule compliance, development of more effective interactions, and improved ability to decode others’ emotional states to respond appropriately and functionally.

What can parents do?

To facilitate intervention, parents must be trained to understand and manage their children’s behavior and to become the supporters the child needs.

ENHANCE YOUR CHILD PSYCOTHERAPY SKILLS

COGNITIVE BEHAVIORAL PLAY THERAPY TRAINING

Oppositional Defiant Disorder — Parent Training

What is Parent Training?

Parent Training is a competence-based intervention model that starts from the assumption that families are able to manage and address the problem, and that every family has strengths and can learn.

When Parent Training is integrated into Cognitive Behavioral Play Therapy, it emphasizes the importance of involving parents in the playroom setting. Parents have the opportunity to observe and progressively implement interventions to shape adaptive behaviors in the presence of the therapist. It emphasizes parents’ capacity to adapt and to learn, and proposes modifying relational styles and attitudes that negatively influence children’s behaviors.

Parents, in this way, have the opportunity to:

- Learn new skills

- Learn and practice specific techniques

- Receive individualized and continuous feedback from the therapist to help them become more aware

- Learn to interpret more accurately their children’s emotions, concerns, and communication as expressed through play

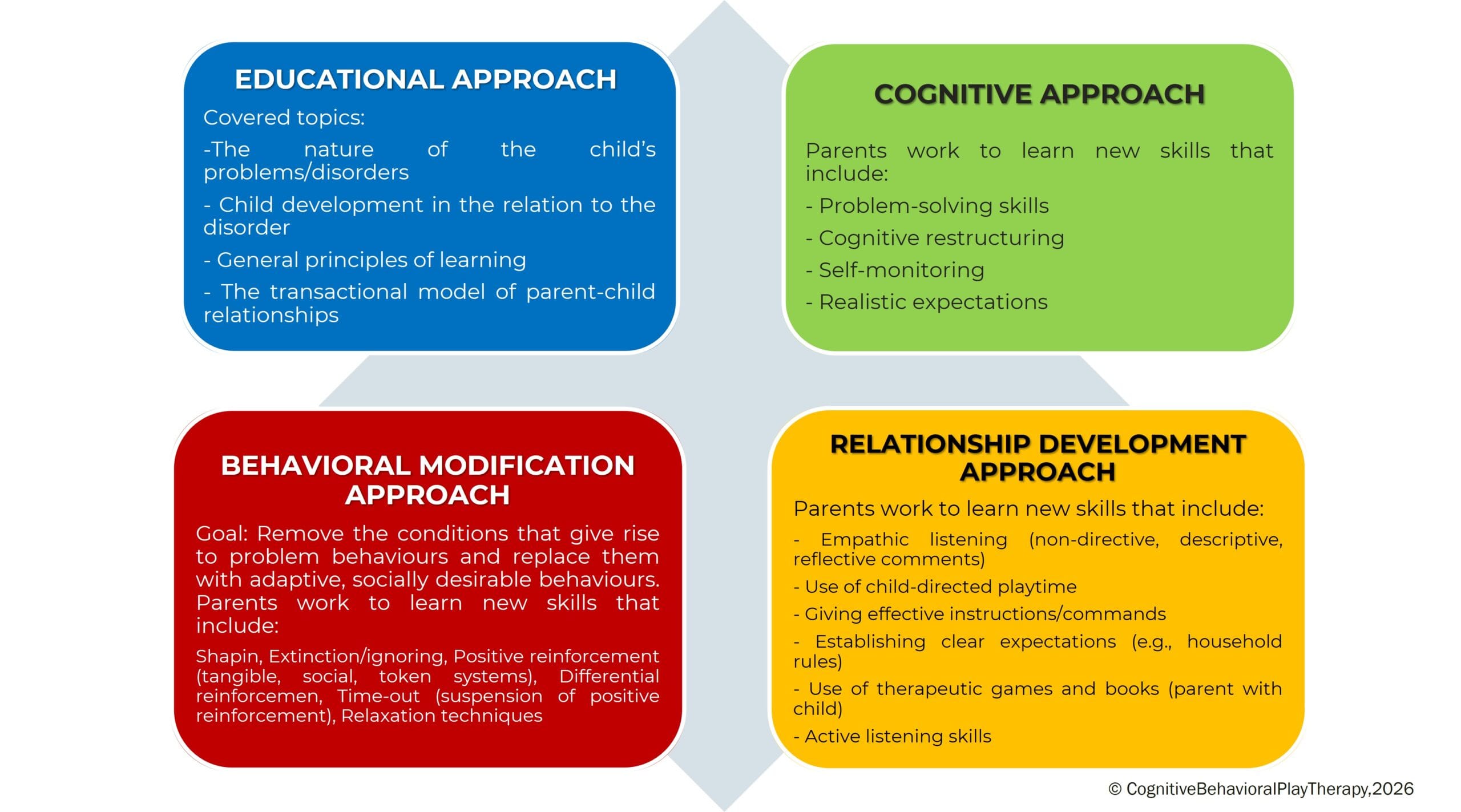

This program, called PARENT TRAINING CBPT, follows an integrated and innovative approach founded on the following approaches:

How is Parent Training Structured in Cognitive Behavioral Play Therapy?

Although the main work is with the child, it is important to meet periodically with the parents. Parental involvement in Cognitive Behavioral Play Therapy is important both during assessment and during treatment. A pathway parallel to the child’s therapy is provided, where the fundamental role of parents in influencing their children’s, maladaptive behaviors is emphasized. Parents are often encouraged to strengthen and reinforce the child’s adaptive behavior so that treatment continues outside therapy (for example, they are trained to use appropriate reinforcement of adaptive behaviors and extinction of maladaptive ones).

Who is it addressed to? It is addressed to both parents.

How long? Typically carried out in 6 to 14 sessions, organized as one 1-hour meeting per week.

The pathway is structured in phases:

- ASSESSMENT PHASE: The problem is analyzed, the parenting style is adapted, and the objective is defined. In this phase parents receive information about the causes and consequences of their children’s dysfunctional behaviors and learn to establish clear and consistent rules.

- LEARNING PHASE: In this phase work is done to define new learnings of all those fundamental skills to support the child’s change. Parents have the opportunity to learn and practice “the techniques” through practice sessions in which the therapist takes on the role of the child, guiding and instructing the parents. In particular, work focuses on:

– mastery of prerequisites;

– modeling of skills;

– role-playing;

– errorless learning;

– successive approximations (shaping);

– feedback (verbal and social reinforcers, token economy);

– practice.

- PRACTICE PHASE: In this phase play sessions with their own children are planned. The skills learned are put into practice. Parents learn to recognize and prevent situations that cause their children’s difficult behaviors and to use the same problem-solving strategies in different situations. After some practice moments with the therapist, parents begin to hold play sessions with their own children, individually, under the therapist’s supervision.

- REVIEW PHASE: Parents discuss with the therapist the play sessions carried out at home to learn how to generalize what they have learned. The aspects that parents feel they did well are discussed and possible problems that arose are addressed. In this phase the therapist helps parents generalize all the interventions learned and the parenting skills acquired during training. Each week some time is dedicated to using what they have learned in everyday life and homework assignments are given aimed at using the techniques.

- CONCLUSION PHASE: This occurs when the therapeutic objectives have been achieved and parents have acquired a good level of competence regarding play activities and parenting skills. Often therapy is concluded gradually, with the frequency of meetings reduced to alternate weeks, then monthly, and so on.

Objectives of Parent Training

This pathway helps the parent interact effectively with their child by developing functional behavioral and communicative habits and techniques. The aim of the intervention is to remove the conditions that give rise to problem behaviors and to replace them with desirable behaviors from an adaptive and social point of view. The objectives are focused on preventing dysfunctions, promoting well-being, and improving crisis conditions.

The objectives of the work with parents are:

- Increase their understanding of the child’s problematic behavior

- Establish more realistic expectations

- Increase warmth, trust, and acceptance toward the child

- Understand the importance of interaction through play

- Communicate more effectively with their children

- Develop greater confidence as parents and reduce the frustrations experienced with their children

- Develop greater patience to create more realistic expectations

- Discuss personal reactions with the therapist to develop a greater degree of understanding of their own feelings and behaviors

- Learn how to become better problem solvers of family conflicts and develop greater motivation toward change

Bibliography

- American Psychiatric Association (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders — Fifth Edition (DSM-5). Italian translation.

- Abdollahian, E., Mokhber, N., Balaghi, A., & Moharrari, F. (2013). The effectiveness of cognitive-behavioral play therapy on the symptoms of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children aged 7–9 years. ADHD Attention Deficit and Hyperactivity Disorders, 5(1), 41–46.

- Antshel, K. M., Faraone, S. V., & Gordon, M. (2012). Cognitive Behavioral Treatment Outcomes in Adolescent ADHD. Journal of Attention Disorders, 18(6), 483-495.

- Favaro, A., & Sambataro, F. (2021). Manuale di psichiatria. Piccin.

- Geraci, M. A. (2022). La play therapy cognitivo-comportamentale. Armando Editore.

- Geraci, M. A. (2023). Comprendere il mondo dei bambini giocando. Armando Editore.

- Geraci, M. A. (2024). Il mondo della dottoressa Lulù. CBPT Books (Amazon series).

- Harris, K. R., Danoff Friedlander, B., Saddler, B., Frizzelle, R., & Graham, S. (2005). Self-Monitoring of Attention Versus Self-Monitoring of Academic Performance: Effects Among Students with ADHD in the General Education Classroom: Effects Among Students with ADHD in the General Education Classroom. The Journal of Special Education, 39(3), 145-157.

- Kaduson, H. G., Cangelosi, D., & Schaefer, C. E. (Eds.). (1997). The playing cure: Individualized play therapy for specific childhood problems. Jason Aronson.

- Knell, S. M. (1993). Cognitive Behavioral Play Therapy. J. Aronson.

- Pandolfi, E. (2010). I Disturbi Esternalizzanti nell’Infanzia: fattori di rischio e traiettorie di sviluppo. Semestrale, School of Specialization in Cognitive Psychotherapy and Association of Cognitive Psychology, 50.

- Raggi, V.L., Chronis, A.M. Interventions to Address the Academic Impairment of Children and Adolescents with ADHD. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev 9, 85–111 (2006).

- Schaefer, C. E., & Drewes, A. A. (Eds.). (2013). The therapeutic powers of play: 20 core agents of change (2nd ed.). John Wiley & Sons.