SELECTIVE MUTISM: COGNITIVE BEHAVIORAL PLAY THERAPY

Selective mutism is an anxiety disorder that can make it difficult for some children to speak in certain social situations, even though they are perfectly able to do so in other contexts. This behavior can have a significant impact on school performance, social interactions, and the child’s emotional well-being. However, there are therapeutic approaches that can help manage selective mutism and enable the child to overcome their fears. If left untreated, selective mutism persists and causes significant impairment in the child’s social and emotional development.

Children with selective mutism are able to speak normally at home or with trusted people, and to understand spoken language, but they withdraw in social contexts such as at school or with strangers. It is not simple shyness; it is a deep anxiety that blocks the child’s ability to speak in specific situations.

How does Selective Mutism present?

Selective mutism mainly presents as a persistent refusal or extreme difficulty speaking in specific social situations, despite the child being fully capable of speaking in other contexts.

Here are some ways selective mutism can manifest:

- The child may be completely silent in certain social situations, such as at school or in public, even though they can communicate verbally in other contexts, such as at home with family.

- The child may resist speaking with people they do not know well, such as teachers, classmates, or strangers. Even if they want to communicate, anxiety can block them from doing so.

- Some children with selective mutism may express themselves through nonverbal communication, such as gestures, body language, or drawings. This can be a way for them to communicate when they feel too anxious to speak. They may also show signs of anxiety, including a flat or unsmiling facial expression, lack of eye contact, extreme shyness, tantrums, difficulty with changes, sleep problems, and an irritable or depressed mood.

- The child may actively avoid social situations in which they feel anxious about speaking, trying to avoid them or spend as little time as possible in them.

- Common physical symptoms include stomachaches, headaches, nausea, and increased sensory sensitivity.

When does Selective Mutism appear?

The average age of onset is between 3 and 4 years, although diagnosis is usually made during school age. For children with a history of selective mutism, verbal output often remains lower than average and shyness and social anxiety frequently persist into adolescence and adulthood, even when selective mutism remits.

What causes Selective Mutism?

Causes may include genetic, environmental, and social factors. Traumatic events or a family environment that limits communication can contribute to the disorder.

Selective Mutism and Cognitive Behavioral Play Therapy

Cognitive Behavioral Play Therapy (CBPT) has proven effective in treating selective mutism because it provides the child with tools to face their fears and anxieties. It offers the opportunity to participate in change, to experience a sense of mastery and control over communication, and to learn more adaptive responses to situations that might automatically trigger silence.

By actively involving parents in the therapeutic process, Cognitive Behavioral Play Therapy also creates a supportive environment that promotes the child’s progress. Parents learn to recognize and address the child’s anxiety, providing continuous support throughout the recovery process.

Cognitive Behavioral Play Therapy is a structured, brief, goal-oriented therapy whose objectives are shared with the child and family. The child is welcomed into a play setting aimed at creating the therapeutic alliance, and parents follow a parallel path focused on learning and strengthening parenting skills.

The intervention is organized into the following phases:

- Orientation Phase: This is the initial phase of Cognitive Behavioral Play Therapy. There is significant emphasis on preparing both the child and the parents. It is crucial to arrange an initial meeting between the therapist and the parents, without the child present, to thoroughly review history and background information. This allows parents to share their perception of the child’s problem. During these initial meetings, the therapist helps parents prepare the child for the first session. In this phase, the ongoing role of parents and other significant adults in the assessment and treatment process is also explained. Although the focus is on the child during Cognitive Behavioral Play Therapy, the therapist continues to interact regularly with parents to provide support and evaluate progress toward therapeutic goals.

- Assessment Phase: This phase focuses on gathering crucial information to establish therapy goals. In addition to interviews with parents, a key element is observation of the child’s play. Various tools are used during this phase, including questionnaires administered to parents, assessment of the child’s play, assessment of family play, a sentence-completion task with puppets, and other measures personalized by the therapist. The therapist may establish a baseline for the frequency of the child’s behaviors, allowing changes in behavior to be evaluated over the course of treatment.

- Case Conceptualization Phase: Cognitive Behavioral Play Therapy begins with analysis of the data collected during assessment, with the aim of planning an effective treatment and providing a logical framework for developing and achieving therapeutic goals. The process starts by explaining selective mutism and analyzing individual, relational, and environmental factors related to the parents’ concerns. The emotional side, thoughts, physical sensations, and coping strategies used by the child are examined. This phase also includes analysis of protective, risk, and maintaining factors that contribute to the child’s behavior.

- Intervention Phase: The intervention phase of Cognitive Behavioral Play Therapy focuses on using CBT techniques that help the child with selective mutism develop more adaptive responses to problems, situations, and stressors. The emphasis is on learning more adaptive thoughts and behaviors. Methods used include modeling, role playing, bibliotherapy, generalization, and relapse prevention. Interventions are often traditional cognitive techniques adapted through play tools such as drawing and expressive arts, listening to stories featuring protagonists in therapeutic storytelling, or interacting with puppets that face similar situations. Treatment includes interventions aimed at helping the child generalize behaviors learned during sessions to other contexts and working on relapse prevention. Although the primary focus is on the child, it is important to maintain regular meetings with parents to monitor progress, assess and intervene in parent–child interactions, and provide guidance on areas of concern.

- Conclusion Phase: Both the child and the family are actively involved in the final phase of therapy. During this period, the child faces feelings related to the end of therapy while the therapist highlights the changes that have occurred and consolidates the learning process. Final sessions may be spaced out over time, moving from weekly to biweekly or monthly meetings. This helps the child perceive their ability to manage life without the therapist. The therapist provides positive reinforcement for the child’s progress between sessions and seeks to normalize the separation experience. After the conclusion of the intervention, follow-ups are scheduled at 3 months, 6 months, 12 months, and 24 months to verify the effectiveness of the intervention.

What are Therapeutic Goals for Selective Mutism?

Cognitive Behavioral Play Therapy can be particularly suitable for children with selective mutism because it gives them:

- the opportunity to participate in change

- the experience of a sense of mastery

- control over communication

- the ability to learn more adaptive responses to situations that might automatically induce silence

Active participation in treatment is important in a disorder where the refusal to communicate is entirely under the child’s control. Children with selective mutism have control over their silence, so to change they must gain control over their communication.

What Parents can do?

It is important for parents to:

- Understand that selective mutism is an anxiety disorder and not a choice by the child.

- Be patient and support the child without pressure.

- Collaborate with therapists and teachers to create a supportive environment.

ENHANCE YOUR CHILD PSYCOTHERAPY SKILLS

COGNITIVE BEHAVIORAL PLAY THERAPY TRAINING

Parent Training in Selective Mutism

What is Parent Training?

Parent Training is a competence-based intervention model that starts from the assumption that families are capable of addressing and managing the problem, that every family has strengths, and that parents can learn new skills.

When integrated into Cognitive Behavioral Play Therapy, parent training emphasizes the importance of involving parents in the playroom setting. Parents have the opportunity to observe and progressively implement interventions to shape adaptive behaviors in the presence of the therapist. The approach highlights parents’ capacity to adapt and learn, and aims to modify relational styles and attitudes that negatively affect children’s behavior.

Through this approach, parents have the opportunity to:

- Learn new skills

- Practice specific techniques

- Receive individualized, ongoing feedback from the therapist to increase their awareness

- Improve their ability to interpret their children’s emotions, concerns, and communication as expressed through play

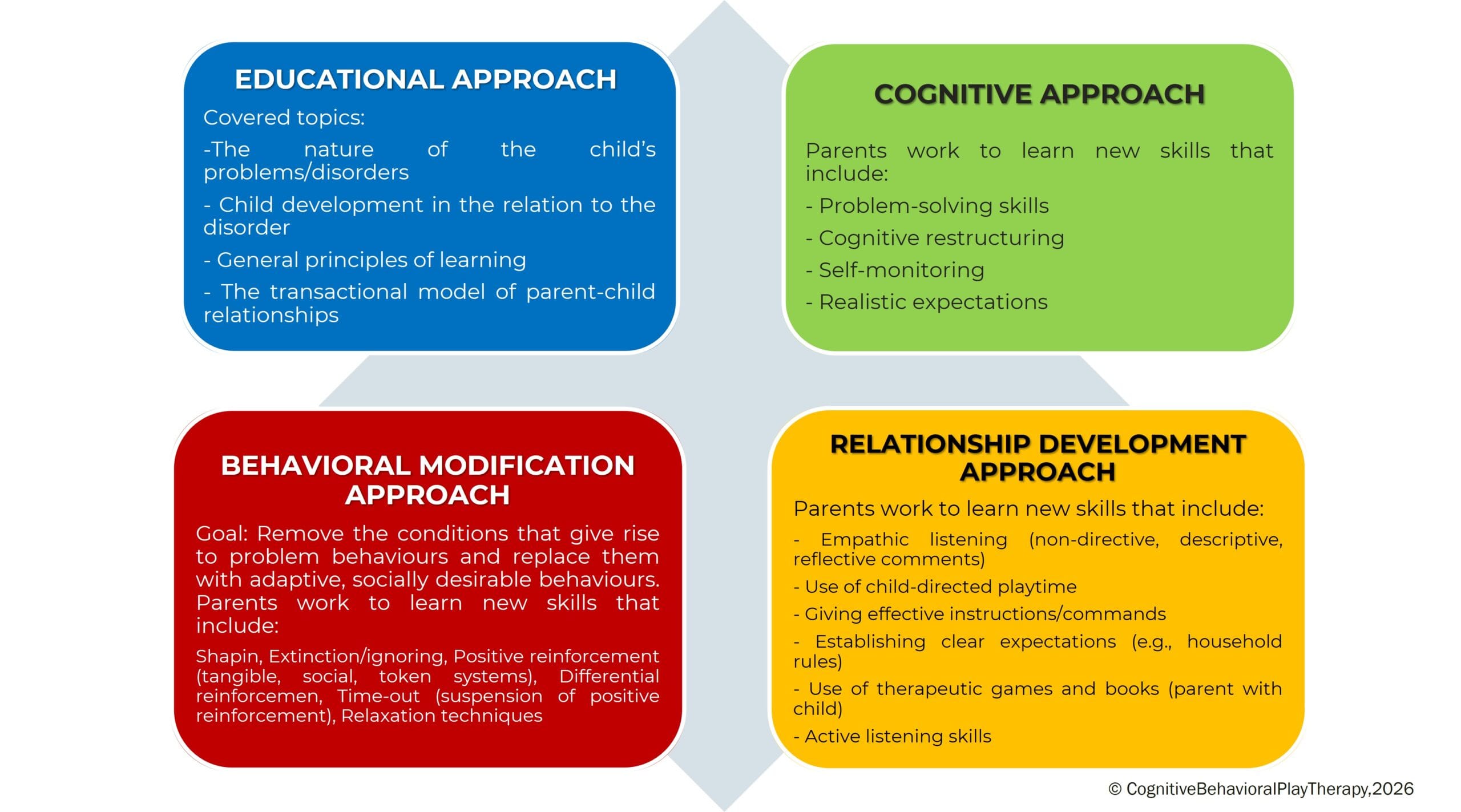

This program, called PARENT TRAINING CBPT, follows an integrated and innovative approach founded on the following approaches:

Parent Training Structure in Cognitive Behavioral Play Therapy

Although the primary work is with the child, it is important to meet periodically with parents. Parental involvement in Cognitive Behavioral Play Therapy is essential both during assessment and treatment. A parallel pathway to the child’s therapy is provided, emphasizing the fundamental role parents play in influencing their children’s maladaptive behaviors. Parents are often encouraged to reinforce adaptive child behaviors so that treatment continues outside the therapy setting (for example, they are trained to use appropriate reinforcement for adaptive behaviors and extinction for maladaptive ones).

Target audience: Both parents.

Typical duration: Usually between 6 and 14 sessions, organized as one 1-hour meeting per week.

The program is structured in the following phases:

- Assessment Phase: The problem is analyzed, parenting style is adapted, and therapeutic goals are defined. In this phase parents receive information about the causes and consequences of their child’s dysfunctional behaviors and learn to establish clear, consistent rules.

- Learning Phase: This phase focuses on teaching the new skills necessary to support the child’s change. Parents learn and practice specific techniques through role-play practice sessions in which the therapist acts as the child, guiding and instructing the parents.

Key targets include:

– mastery of prerequisites;

– modeling of skills;

– role-playing;

– errorless learning;

– successive approximations (shaping);

– feedback (verbal and social reinforcers, token economy);

– repeated practice.

- Practice Phase: Parents carry out play sessions with their own children to apply the skills learned. They learn to recognize and prevent situations that trigger difficult behaviors and to use the same problem-solving strategies across different contexts. After initial practice moments with the therapist, parents begin to run individual play sessions with their children under the therapist’s supervision.

- Review Phase: Parents discuss at length with the therapist the home play sessions to learn how to generalize what they have learned. Strengths and any problems that arose are reviewed. The therapist helps parents generalize the interventions and the parenting skills acquired during training. Each week some time is dedicated to applying learned techniques in everyday life and homework assignments are given to practice the strategies.

- Conclusion Phase: This phase occurs when therapeutic goals have been met and parents have achieved a satisfactory level of competence in play activities and parenting skills. Therapy is often tapered gradually, reducing session frequency to every other week, then monthly, and so on.

Objectives of Parent Training

This program helps parents interact effectively with their child by developing functional behavioral and communicative habits and techniques. The intervention aims to remove conditions that give rise to problem behaviors and replace them with adaptive, socially desirable conduct. Objectives focus on preventing dysfunction, promoting well-being, and improving crisis conditions.

Specific goals for work with Parents

- Increase understanding of the child’s problematic behavior.

- Set more realistic expectations.

- Increase warmth, trust, and acceptance toward the child.

- Recognize the importance of interaction through play.

- Communicate more effectively with their children.

- Develop greater parental confidence and reduce frustrations experienced with their children.

- Cultivate greater patience to create more realistic expectations.

- Discuss personal reactions with the therapist to gain deeper understanding of their own feelings and behaviors.

- Learn to become effective problem solvers of family conflicts and develop stronger motivation for change.

Bibliografia

Favaro, A., & Sambataro, F. (2021). Manuale di psichiatria. Piccin.

Geraci M. A. (2022). La play therapy cognitivo-comportamentale. Armando Editore. Roma

Geraci M. A. (2023). Comprendere il mondo dei bambini giocando. Armando Editore. Roma

Geraci M. A. (2024). Il mondo della dottoressa Lulù. Collana Amzon – CBPT Books.

Knell S. M. (1993). Cognitive Behavioral Play Therapy. J. Aronson

American Psychiatric Association (2013). Manuale diagnostico e statistico dei disturbi mentali – Quinta edizione. DSM-5. Tr.it.