SPECIFIC PHOBIA: COGNITIVE BEHAVIORAL PLAY THERAPY

What is Specific Phobia?

Specific phobia is an anxiety disorder characterized by intense, disproportionate anxiety and fear in response to particular objects or situations, referred to as phobic stimuli. The most common phobic stimuli are:

- Animals (spiders, insects, dogs)

- Situational (airplanes, elevators, enclosed spaces)

- Natural environment (heights, storms, water)

- Blood, injections, and injuries

To diagnose specific phobia, the reaction must differ from normal, transient fears commonly seen in the population. The intensity of fear may vary depending on proximity to the feared object or situation and can occur in anticipation of or during actual exposure. Fear and anxiety are disproportionate to the real danger posed by the specific object or situation and to the sociocultural context.

How Specific Phobia Manifests?

In children, specific phobia can present with:

- Temper tantrums and/or angry outbursts

- Freezing (becoming immobile)

- Clinging to a parent

Adults with this disorder typically actively avoid the phobic situation or object that elicits intense fear or anxiety. Active avoidance consists of intentional behaviors aimed at preventing or minimizing contact with the feared stimulus. Children often cannot conceptualize active avoidance, so clinicians should gather additional information from parents, teachers, or others who know the child well.

When Specific Phobia Appears?

Specific phobia usually develops in early childhood, most often with onset before age ten. The mean age of onset is between 7 and 11 years, with an average of around 10 years. Girls are more frequently affected than boys, with a ratio of approximately 2:1. Excessive fears are common in young children but are generally transient and cause only moderate impairment, so they are considered developmentally appropriate. For children, it is important to assess the degree of impairment and the duration of fear, anxiety, and avoidance, considering whether these symptoms are typical for the child’s developmental stage.

What Causes Specific Phobia?

Specific phobia can sometimes develop after a traumatic event (e.g., being attacked by an animal or becoming trapped in an elevator), from observing a traumatic event happening to others (e.g., witnessing someone drown), or following an unexpected panic attack that later becomes associated with the feared situation. Contributing factors include:

Temperamental factors: risk factors such as negative affectivity or behavioral inhibition.

Environmental factors: risk factors such as parental overprotection, loss or separation from a parent, and physical or sexual abuse. Negative or traumatic encounters with the feared object or situation sometimes precede phobia development.

Genetic and physiological factors: there may be genetic susceptibility for certain phobia categories; for example, blood-injection-injury phobia appears to have a stronger hereditary component. Unlike some other anxiety disorders that follow a fluctuating chronic course, specific phobia severity is often considered relatively stable.

Childhood Specific Phobia and Cognitive Behavioral Play Therapy

CBPT is an approach that targets mood by first modifying behaviors and thought patterns. When anxiety and fear interventions incorporate play, children engage more readily. As noted in the literature: “fears can often be managed through reassurance, education, experience, and/or exploration via play (for example, games involving monsters, scary animals, or ghosts” (Augustyn & Hermann, 2017).

The goal of CBPT with fearful children is to help them manage their fears and return to emotional, behavioral, cognitive, and physical well-being.

CBPT is a structured, brief, goal-oriented therapy whose goals are shared with the child and family. The child is welcomed into a play setting designed to build the therapeutic alliance, while parents follow a parallel program aimed at learning and strengthening parenting skills.

The intervention is organized into the following phases:

- Orientation Phase: The initial phase emphasizes preparing both the child and the parents. It is crucial to hold an initial meeting between the therapist and the parents without the child to review history and background information in detail. This allows parents to share their perception of the child’s problem. During these initial meetings, the therapist helps parents prepare the child for the first session and explains the ongoing role of parents and other significant adults in assessment and treatment. Although the focus is on the child, the therapist continues to interact regularly with parents to provide support and evaluate progress toward therapeutic goals.

- Assessment Phase: This phase focuses on collecting information essential for setting therapy goals. In addition to parent interviews, a key element is observation of the child’s play. Various tools are used, including parent questionnaires, assessment of the child’s play, family play assessment, puppet-based sentence completion tasks, and other measures tailored by the therapist. The therapist may establish a baseline frequency for the child’s behaviors to evaluate behavioral change over the course of treatment.

- Case Conceptualization Phase: CBPT begins with analysis of the data gathered during assessment to plan an effective treatment and provide a logical framework for developing and achieving therapeutic goals. The clinician explains specific phobia, analyzes individual, relational, and environmental factors related to parental concerns, and examines the child’s emotions, thoughts, physical sensations, and coping strategies. This phase also includes analysis of protective, risk, and maintaining factors contributing to the child’s behavior.

- Intervention Phase: The intervention phase focuses on using CBT techniques to help the child with specific phobia develop more adaptive responses to problems, situations, and stressors. Emphasis is placed on learning more adaptive thoughts and behaviors. Methods include modeling, role-playing, bibliotherapy, generalization, and relapse prevention. Cognitive interventions are often adapted through play tools such as drawing and expressive arts, therapeutic storytelling featuring protagonists with similar challenges, or interaction with puppets confronting comparable situations. Treatment includes strategies to help the child generalize skills learned in sessions to other contexts and to work on relapse prevention. Although the primary focus is the child, regular meetings with parents are important to monitor progress, assess and intervene in parent–child interactions, and provide guidance on relevant areas.

- Termination Phase: Both the child and the family are actively involved in termination. During this final period, the child processes feelings related to ending therapy while the therapist highlights changes and consolidates learning. Final sessions may be spaced out over time, moving from weekly to biweekly or monthly meetings to help the child experience coping without the therapist. The therapist provides positive reinforcement for progress between sessions and normalizes the separation experience. Follow-up assessments are scheduled at 3, 6, 12, and 24 months to evaluate intervention effectiveness.

What are the therapeutic goals?

In CBPT, goals are defined collaboratively with children and their families. For specific phobia, typical objectives include:

- Facilitating emotional expression and regulation

- Reducing symptoms and problematic behaviors

- Decreasing avoidance or escape behaviors

- Developing new coping skills and strategies

- Teaching children methods and techniques to face and overcome the specific fear

- Strengthening resources and strengths

- Developing problem solving abilities

- Providing psychoeducation to both parents and child

According to Lewis, Amatya, Coffman, and Ollendick (2015), empirically supported methods for treating anxiety disorders include CBT, systematic desensitization, graduated in vivo exposure, cognitive restructuring, reinforcement practice, and participant modelling.

The aim of each session is to increase anxiety levels while the child engages in relaxation activities so that the fear response is attenuated and ultimately extinguished.

What Parents Can Do?

Parents and caregivers are often the first to witness a child’s fears, and their responses can shape how those fears are managed. When a parent responds to a child’s distress with compassion and offers to face the fear together, the child learns that it is possible to try things that may help them feel better.

However, parents commonly believe they are protecting their children when they comfort them and avoid the things that frighten them. Although these loving acts provide immediate relief, they do not produce lasting change. A child who is not helped to confront a phobia will continue to suffer.

Parent education may be necessary to help caregivers understand that some fears and phobias have a genetic basis, while others arise directly from a frightening experience or indirectly from observing others’ fearful reactions in specific situations. It is also useful to know that there is a high concordance of fears within families.

With this information, parents should:

- Do their best to give children experiences that help inoculate them against the same fears the parents themselves may have.

- Learn how to reinforce a child’s attempts to face their fears and recognize how well‑intentioned efforts to protect or comfort can interfere with extinction of the fear.

- Understand that the goal of any plan is to eliminate avoidance of the feared object or situation, and that any progress the child makes toward the feared situation should be reinforced.

To be active agents in the process, parents are advised to show understanding for the child’s experience, even when those reactions may seem strange or unfamiliar to them.

ENHANCE YOUR CHILD PSYCOTHERAPY SKILLS

COGNITIVE BEHAVIORAL PLAY THERAPY TRAINING

Parent Training in Specific Phobia

What is Parent Training?

Parent Training is a competency‑based intervention model that assumes families are capable of addressing and managing problems, that every family has strengths, and that caregivers can learn new skills.

When Parent Training is integrated into Cognitive Behavioral Play Therapy, it emphasizes the importance of involving parents in the playroom setting. Parents have the opportunity to observe and progressively implement interventions to shape adaptive behaviors in the presence of the therapist. The approach highlights parents’ capacity to adapt and learn, and aims to modify relational styles and attitudes that negatively influence children’s behavior.

Parent Roles and Opportunities

Through this program, parents can:

- Learn new skills

- Acquire and practice specific techniques

- Receive individualized, ongoing feedback from the therapist to increase self‑awareness

- Learn to interpret more accurately their children’s emotions, concerns, and communications as expressed through play

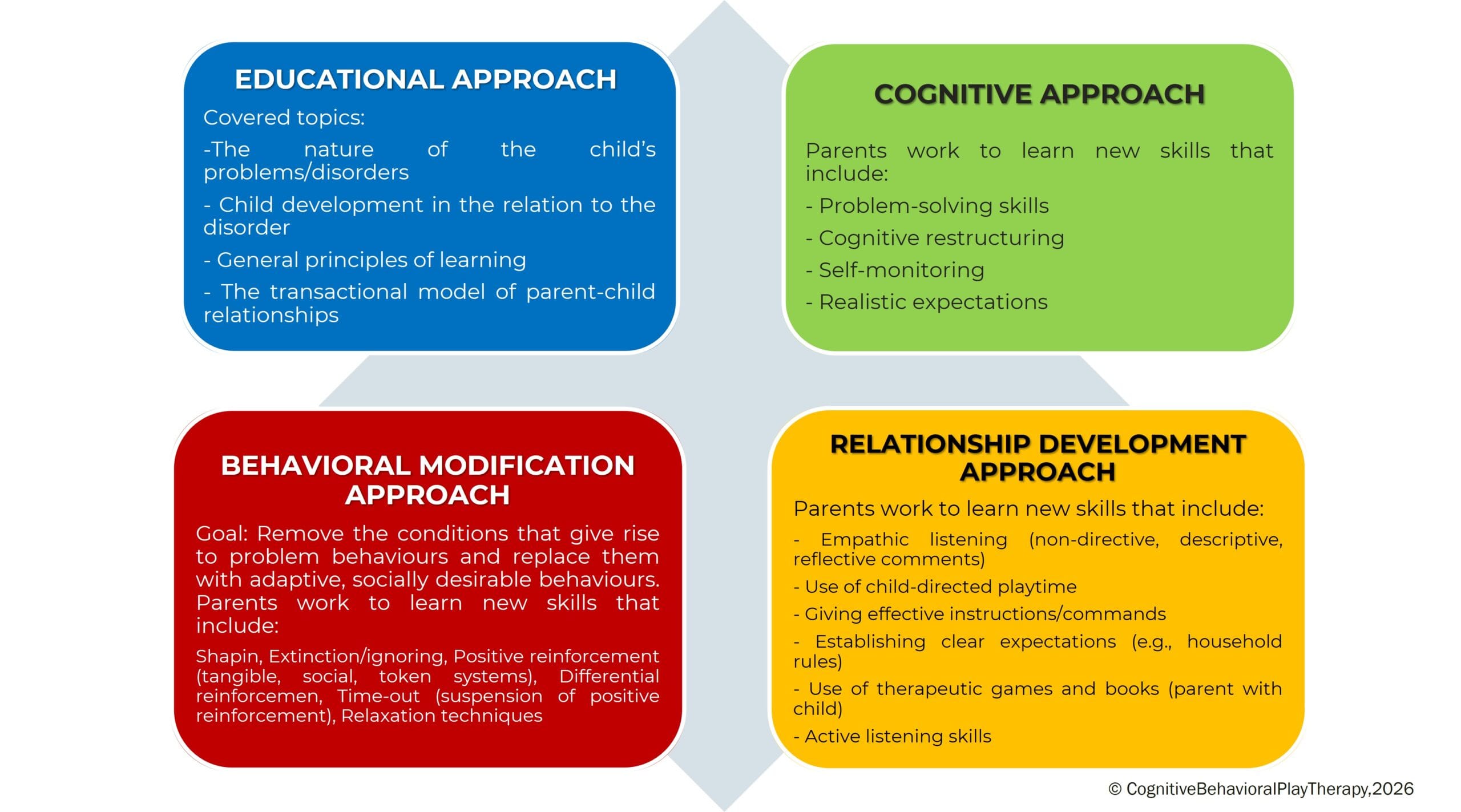

This program, called PARENT TRAINING CBPT, follows an integrated and innovative approach grounded in the following frameworks:

How is the Parent Training structured in Cognitive Behavioral Play Therapy?

Parent Training is a competency‑based intervention model that assumes families can address and manage problems, that every family has strengths, and that caregivers can learn new skills.

When integrated into Cognitive Behavioral Play Therapy, Parent Training emphasizes involving parents in the playroom setting. Parents observe and progressively implement interventions to shape adaptive behaviors while the therapist is present. The approach highlights parents’ capacity to adapt and learn and aims to modify relational styles and attitudes that negatively influence children’s behavior. Parents are encouraged to reinforce adaptive child behaviors and to apply treatment strategies outside therapy (for example, using appropriate reinforcement for adaptive behaviors and extinction for maladaptive ones).

Who it is for? The program is intended for both parents or primary caregivers.

Typical duration? Usually consists of 6 to 14 sessions, scheduled weekly, each lasting about one hour.

Structure and Phases of the Program

The Parent Training pathway is organized into the following phases:

- Assessment Phase: Analyze the problem, adapt parenting style, and define treatment goals. Parents receive information about causes and consequences of their child’s dysfunctional behaviors and learn to establish clear, consistent rules.

- Learning Phase: Focus on teaching the core skills needed to support the child’s change. Parents learn and practice specific techniques in guided practice sessions where the therapist role‑plays the child, coaching and instructing the parents. Key training elements include:

– mastery of prerequisites;

– skill modeling; role‑playing;

– errorless learning;

– successive approximations (shaping);

– feedback (verbal and social reinforcers, token economy);

– repeated practice.

- Practice Phase: Parents conduct play sessions with their own children to apply the skills learned. They learn to recognize and prevent situations that trigger difficult behaviors and to use consistent problem‑solving strategies across contexts. After initial practice with the therapist, parents begin to run individual play sessions with their children under therapist supervision.

- Review and Generalization Phase: Parents discuss home play sessions with the therapist to learn how to generalize skills. The therapist helps parents consolidate and transfer the interventions and parenting competencies acquired during training. Weekly assignments encourage application of techniques in everyday life.

- Termination Phase: Occurs when therapeutic goals are met and parents demonstrate competence in play activities and parenting skills. Termination is often gradual, with session frequency reduced to biweekly, then monthly. The process reinforces parental confidence and supports the child’s ability to cope without the therapist.

Objectives of Parent Training

The program helps parents interact effectively with their child by developing functional behavioral and communication habits and techniques. The intervention aims to remove conditions that give rise to problem behaviors and to replace them with socially and adaptively desirable behaviors. Goals focus on preventing dysfunction, promoting well‑being, and improving crisis conditions.

Specific objectives when working with parents include:

- Increase understanding of the child’s problematic behavior.

- Set more realistic expectations.

- Enhance warmth, trust, and acceptance toward the child.

- Recognize the importance of interaction through play.

- Communicate more effectively with their children.

- Build parental confidence and reduce frustration in parenting.

- Develop greater patience and realistic expectations.

- Process personal reactions with the therapist to increase insight into their own feelings and behaviors.

- Learn problem solving and conflict resolution skills for family situations and increase motivation for change.

Selected Bibliography

Favaro, A., & Sambataro, F. (2021). Manuale di psichiatria. Piccin.

Geraci M. A. (2022). La play therapy cognitivo-comportamentale. Armando Editore. Roma

Geraci M. A. (2023). Comprendere il mondo dei bambini giocando. Armando Editore. Roma

Geraci M. A. (2024). Il mindo della dottoressa Lulù. Collana Amzon – CBPT Books.

Knell S. M. (1993). Cognitive Behavioral Play Therapy. J. Aronson

American Psychiatric Association (2013). Manuale diagnostico e statistico dei disturbi mentali – Quinta edizione. DSM-5. Tr.it.